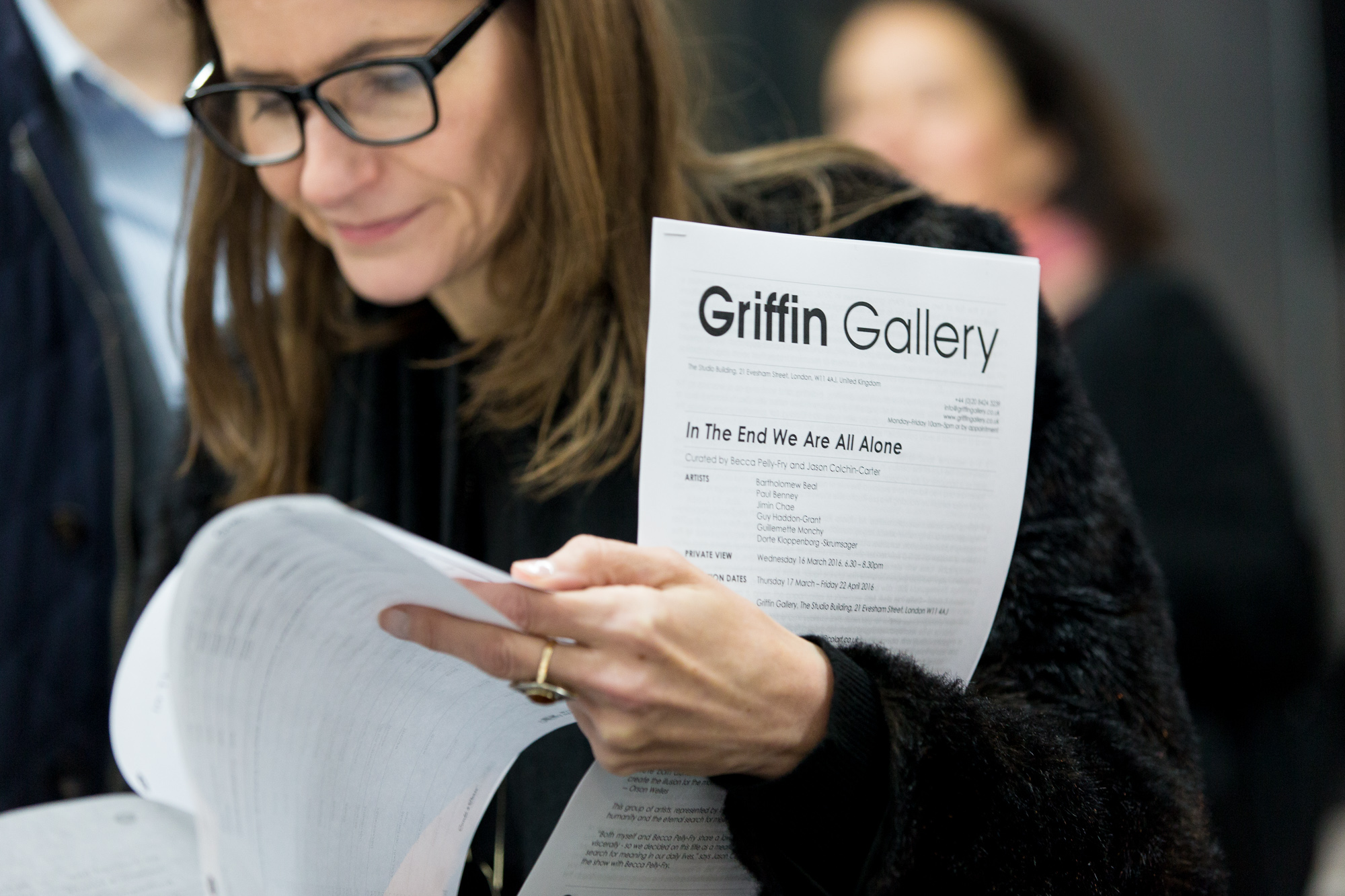

IPA Group Show at the Griffin Gallery co-curated by Jason Colchin Carter and Becca Pell-Fry

March 16 – April 22

‘In the end we are all alone,’ is a quote by Orson Wells from his era defining biopic Citizen Kane. It’s a deliciously enigmatic title for a group show, one that unites those singular, melancholy concepts – end, alone – with inclusive universals: we all. This conceit engenders a second reading and offers us a clue as to how we might approach the works in this show. It speaks of duality: although the inevitable conclusion of this mortal coil is unknowable, it is our common destiny, one we are invited to share. It could be likened to the act of creation, often solitary and difficult, and yet what it produces transcends time altogether. A work of art lives on in the seeing and the sharing. In this context, the show’s title is not as dissonant as it first appears. This feeling of being ‘alone’ activates our search for meaning, and satisfies the desire ‘we all’ have to find respite in the lasting materiality of exceptional works of art, where the artists presence is still manifest.

“Both myself and Becca Pelly-Fry share a love of art work that makes you feel deeply and react viscerally – so we decided on this title as a means to explore the nature of humanity and the eternal search for meaning in our daily lives,” says Jason Colchin-Carter Director of IPA who co-curated the show with Becca Pelly-Fry.

This is the first of two annual group shows in 2016 curated by Colchin-Carter with Isis Phoenix Arts. It promises a budding spring of fresh works set to spark our imaginations; generous works that leave ample room for contemplation and individual interpretation. Like musical prodigies, these artists have been chosen for their capacity to reinterpret traditional mediums and techniques in unexpected ways: Paul Benny, Bartholomew Beal, Jimin Chea, Guillemette Monchy, Dorte Kloppenborg Scrummager and Guy Hadden Grant. Each artist displays a unique and sophisticated approach to their chosen medium, whilst their work conveys narrative content or recurring tropes that seem vaguely familiar. This combination gently initiates us into original ways of seeing. This is an international collective that screams zeitgeist, brought together by a visionary art agency with Colchin-Carter at the helm who, like Simco (Stefan Simchowitz) in the US, is changing the status quo and giving collectors access to some of the brightest rising stars of this generation.

“I see the resurgence of traditional skills like drawing, painting and sculpting as a reaction to the YBA’s turning 50. They are now BA’s and still very relevant, but artists like (Bartholomew) Beal or (Jimin) Chae seem to really strike a chord with collectors looking for something new, where the hand of the artist is really palpable,” says Colchin-Carter.

It is a welcome tonic to the mechanical and deliberately impersonal Postmodernism that dominated the turn of the century in contemporary galleries and museums. Narrative painting was seen as a hangover of the Victorian era, but over the past decades artists like John Currin and Neo Rauch have explored the role of narrative again in fresh and compelling ways, whilst major exhibitions including two pre-Raphaelite shows in 2016, signal a sea change in attitudes.

“With a few obvious exceptions—Pop Art, Photo Realism and artists such as David Hockney—representational or figurative art was largely considered a thing of the past by the end of the 20th century. But in recent years, a number of contemporary painters have begun reaching back to the roots of modern art to find new modes of expression. They are mixing the human figure and other recognizable forms with elements of abstraction and ambiguous narrative in ways not seen before.” says By Paul Trachtman in his article Back to the Figure in the Smithsonian Magazine

It might be tempting to try and categorize these works into a movement such as Neo-Expressionism to which some of the group like Paul Benney are associated, but that would be missing the point. Collectively this IPA show is asking us to reevaluate our relationship to artists who are transforming and advancing the use of traditional mediums and genres, as they conjure up whole new worlds of possibility at their finger tips. A narrative may be embedded in these works, but they are also a psychic configuration of things that do not have visual representation, of a place beyond words. Yes we are alone in death, but some of us choose to shine brightly whilst we live in a myriad of unexpected, inexplicable and profoundly moving ways.

* * * * *

Paul Benney is best known for brooding depictions of lonely figures lost in a stygian world, punctuated by flashes of white light. An original member of the Neo-Expressionist group formed in the early 80s New York East Village, he uses complexity and ambiguity to challenge our interpretation of the visual narrative. In the forward to his monograph Night Painting, Rachel Campbell Johnson says, “Benney paints figures, whilst their meanings can never be quite fixed, embody some sense of our spiritual quest… The landscape is similarly transformed. He may be painting natural phenomena…but their delicate beauty keys in to our sense of an extra dimension.”

Represented in public and private collections around the world including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the National Gallery, Australia, and The National Portrait Gallery, London, with a recent solo show at Serena Morton Gallery, Benney is also one of the UK’s leading portrait artists. His growing list of prominent cultural and political patrons includes almost every member of the Ghetty Family.

“Benney’s recent portrait of Balthazar Getty is a very contemporary take on the classic portrait; the subject casually dressed and sitting on a stool with pale green backdrop,” says Colchin-Carter. For this show we have commissioned his second largest studio work, a vast 14 x 8 ft painting, after his Talking Tongues which was inspired by Goya’s famous painting, all of the subjects have flames coming out of the top of their heads. The new work will have a large single figure and whirlpools with flames”

Like other great narrative painters, DiBenedetto or Angela Dufresne, Benney uses obscurity and historical reference to engage us in a compelling visual narrative. “We approach with a strange sense of déjà vu. We have walked these places before. They belong to the lands inside our heads,” Say Campbell Johnson and she might be referencing a number of artists in this show.

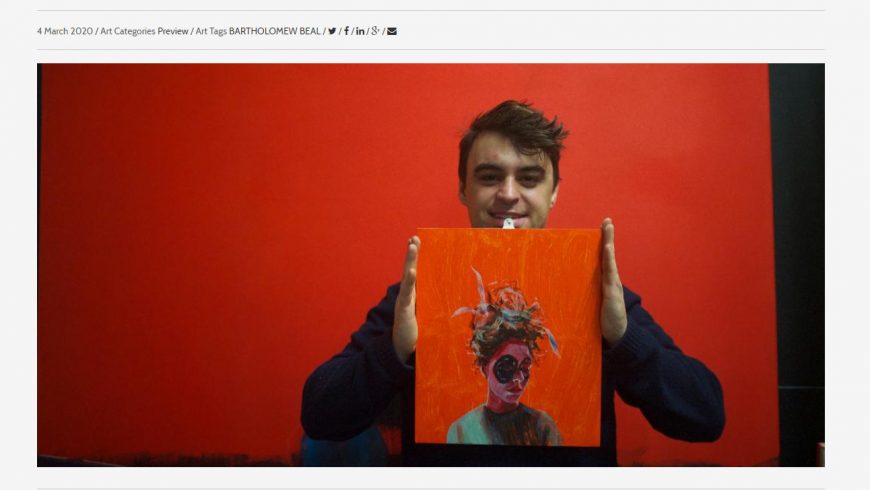

Fresh from his second sell out solo show at the FAS New Bond Street.

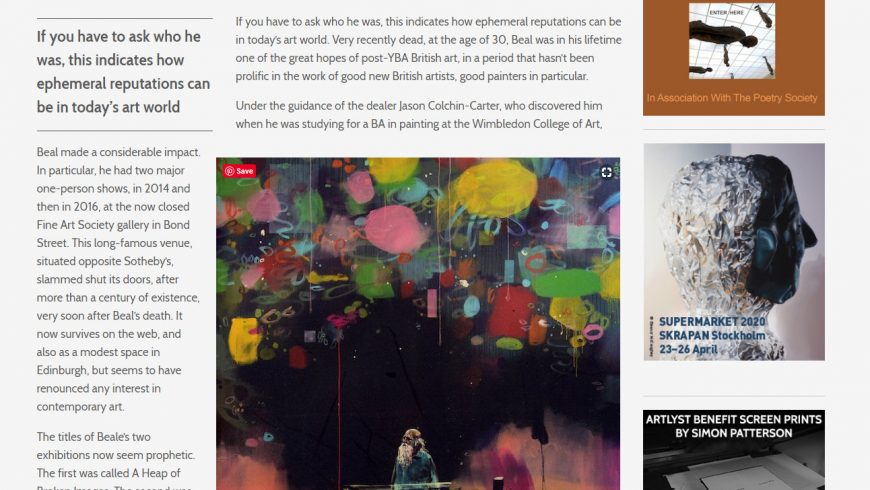

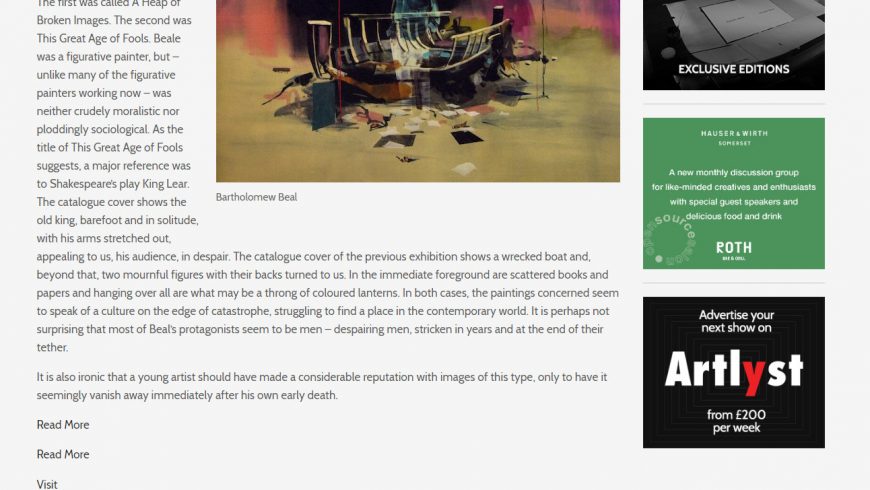

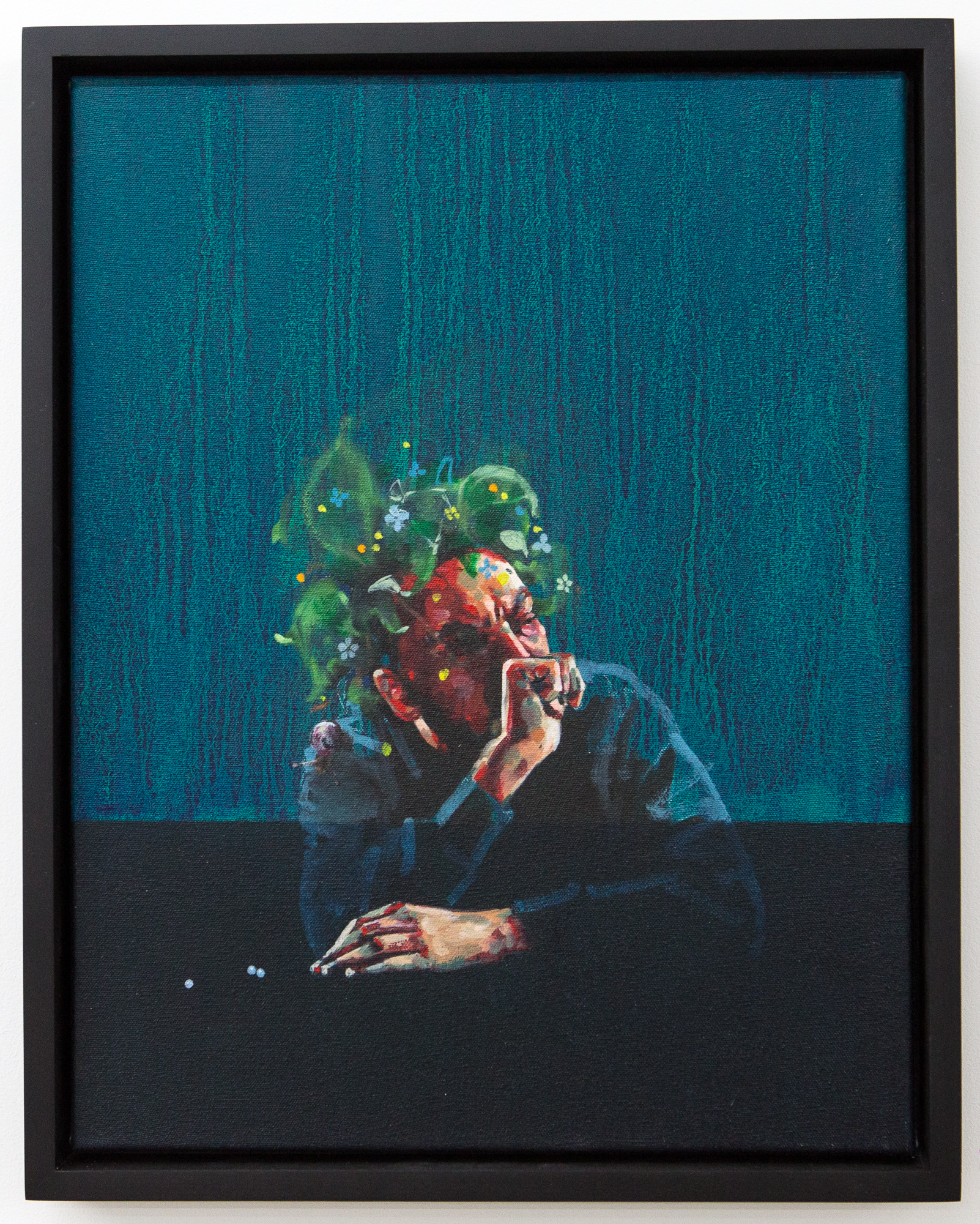

Bartholomew Beal’s tableaus, executed in a vivid and dynamic color palette, illustrate half-formed spaces that reference both the theatre of literary history and the real world’s ever evolving stage. Just like windows, they reveal powerful interior scenes whilst reflecting the viewer therein, leaving elements unfinished for our minds to complete the picture. IP Arts exclusively represents Beal choosing to Collaborate with Galleries. Despite his youth – Beal is only 26 – his natural ability allows him to tackle weighty themes of our human experience, whilst also questioning how this particular screen based society is evolving. With oblique references to virtual windows on the worldwide web through floating panes of translucent colour, he frequently anchors his pieces on the crumpled face of a bearded old man who might be God or King Lear – a fiction or reality. This is not a screen friendly face. Moving seamlessly between the tight exactitude of representational forms and the loose and emotive brushworks of abstraction and color fields, Beal often conceals figures in his work, painting over the ghosts of his own progress.

“Whilst his subjects might be melancholy, his colors are bright and uplifting and he gives the viewer room to make the connection between his literary references and pressing social issues we face today, such as the refugee crisis. We are so excited about his work for this show which includes his first extra large diptych of 240cm X 180cm.”

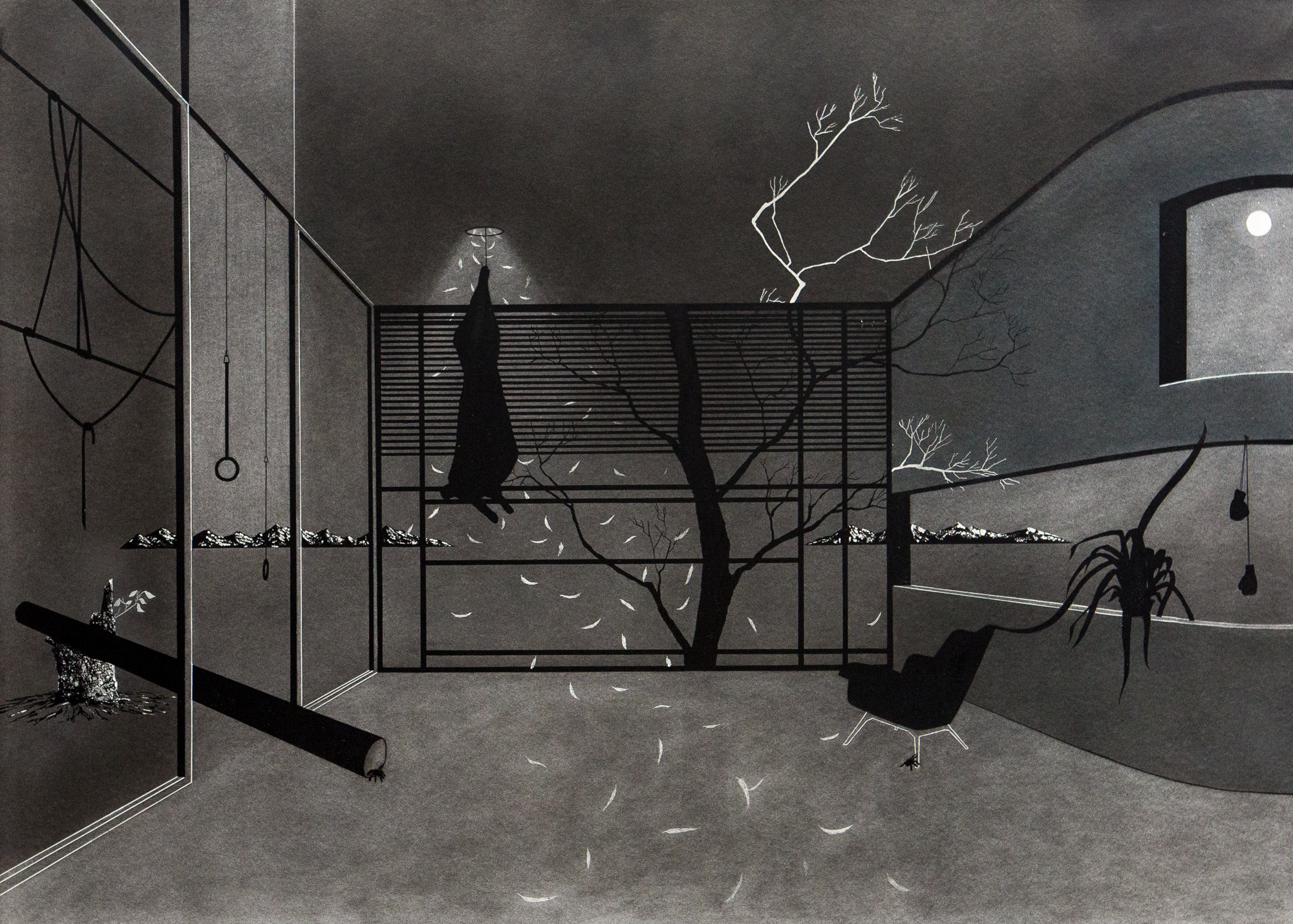

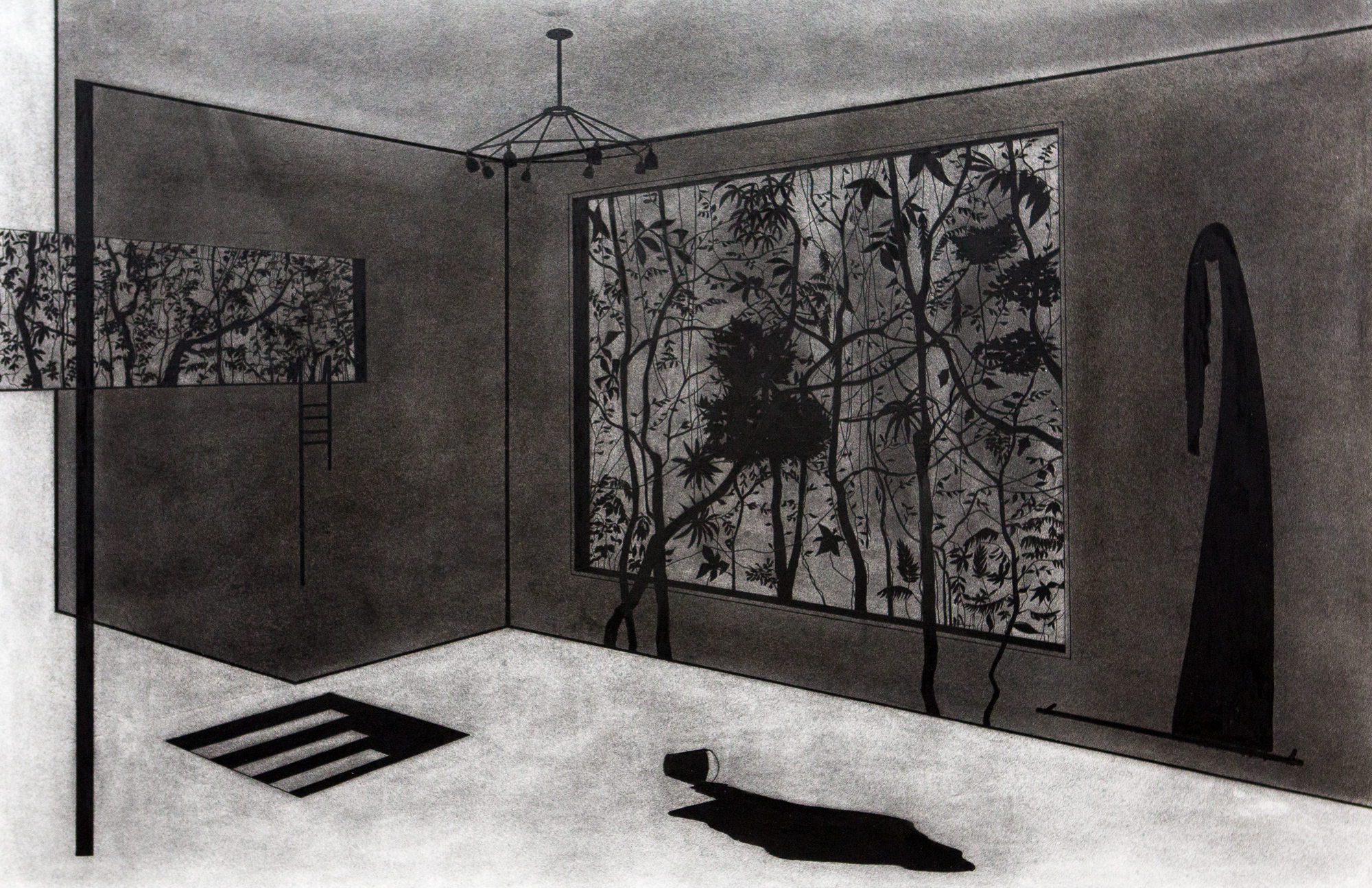

In compliment to Beal’s extraordinary dexterity is Jimin Chae, a Graduate of Chelsea from South Korea. The youngest artist in the exhibition, Chae first caught Colchin-Carter’s eye with a bold triptych executed in Hockneyesque in blocks of colour. Returning from a residency in New York, he currently works from his studio South Korea. “Creating 8 new pieces for this show over the last twelve months, his first triptych which will be on display in a private viewing room so collectors can experience his work at this scale,” says Colchin-Carter. Layering flat bright elements drawn from interiors and the bold outlines of architecture, his work offers us glimpses into an alternative reality held together in a careful, sometimes precarious, balance.

Speaking of precarious, Colchin-Carter signed Guillement Monchy on the day bombs went off throughout Paris in November 2015. From her studio in the north of Paris, Monchy’s practice is centered on mixed media drawings and gouache. These work are ethereal in quality, but quietly charged with the tension that exists between art and reality – a line which is constantly, sometimes dangerously, blurred. Her image source is an expanding and interconnected web of family photos, internet screen shots, classic films and the vestiges of fading memory, which she curates and collates in a form of virtual self-portraiture. She is the author of what she chooses to represent or obscure, oscillating between fact and fiction, imagined and real, and never quite reveals her hand. “Again there is this sense with Monty’s work that nothing is entirely what it seems, and so we are engaged in the search with her. For this show she has taken inspiration from classic French cinema from the 40s and 50s.”

Transitioning us into the three dimensional, is the sculptor Dorte Kloppenborg Scrumsager, who has been working with IPA for three and a half years. “The title Saligia + 1 is Latin for Seven Deadly Sins + 1, so I call it the 8 Deadly Sins. We are showing four complete sets of the 8 Deadly Sins – 32 hand made pieces in total.” Working in clay, Dorte then uses the lost wax casting method to translate her pieces into bronze, which she then polishes using the finest grade sand paper. They are beguiling, mellifluous, and call to mind the biomorphic shapes of great 20th century sculptors like Barbara Hepworth and Bridget McCrum, and yet there is more. With Bacon-like mouths and body parts, the viewer is invited to match each piece with its requisite deadly sin, with the eighth being left entirely open to interpretation.

“The whole fun in this series, and the reason why Dorte hooked me 30 seconds into the pitch, is that it is so culturally inclusive. Everyone will have their own idea of how the shapes relate to the sins and what the eighth one could be,” enthuses Colchin-Carter.

With not a flat surface in sight, these sculptures also act as mirrors – parts of your face reflected and refracted therein. This highly polished finish is indicative of how contemporary artists can harness technical innovations to advance their own practice.

On this point Dorte collaborated with IPA to design and patent a hinge mechanism that gives the collector the option to tilt and position either floor or wall mount each piece. “Not wanting to limit our collectors we created that option!” says Colchin-Carter giving us an insight into the wonderful symbiotic relationship he facilitates between artist and collector.

Guy Haddon-Grant’s bronze series The Pleasure and Terror of Levitation, has also been curated for this show. A graduate of Camberwell Collage, Haddon-Grant manages Nicola Hicks studio and alongside his own sculptural practice which often includes drawing, calling to mind the work of Jenny Saville. Fastidious in his research, his studio is a rich seam of ancient and historical studies that reaches all the way back to the earliest expressions in cave paintings.

This showstopper captures the undulating wave of articulating arms mimicking flight across 13 scale bronze torsos set into a 180cm plinth. “The reason I love this work so much is that although there are 13 pieces, Grant has created them on a very intimate scale with multiple points of perspective. If you stand in front of the piece you only see one torso lifting its arms gracefully like a dancer, but from the side they are all alone…”

* * * * *

“Our strategy is very simple: to give artists that I believe in and am very passionate about the chance to be seen by collectors and clients with major collections and strong institutional ties. The gallery industry can be incredibly daunting for an emerging artist. I try to give them a minimum of two or three years filled with as much possibility and exposure that someone in my position can afford them. I am deeply indebted to Edward Lucie Smith who has generously mentored me for the last four years and given me the confidence to move into new markets, including LA, San Francisco, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea and Hong Kong this year which is incredibly daunting but IPA is ready.” For Colchin-Carter the whole world is an evolving stage – a platform where he strives to celebrate how art is embedded in the fabric of life.

In The End We Are All Alone

Griffin Gallery 16 March – 18 May

Ground Floor Collart Building 12 Beecham Street, London W11 4HA