From the Artlyst article:

Bartholomew Beal: A Heap of Broken Images – Edward Lucie-Smith

The new Masculinities show at the Barbican, excellent and comprehensive as it is, contains – for me at least – one striking omission. There was no work, or group of works, by the young British artist Bartholomew Beal.

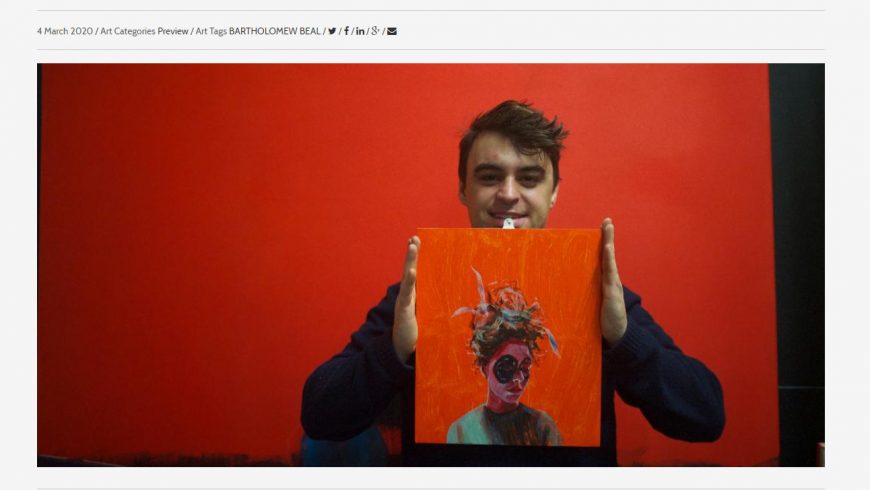

If you have to ask who he was, this indicates how ephemeral reputations can be in today’s art world. Very recently dead, at the age of 30, Beal was in his lifetime one of the great hopes of post-YBA British art, in a period that hasn’t been prolific in the work of good new British artists, good painters in particular.

Under the guidance of the dealer Jason Colchin-Carter, who discovered him when he was studying for a BA in painting at the Wimbledon College of Art, Beal made a considerable impact. In particular, he had two major one-person shows, in 2014 and then in 2016, at the now closed Fine Art Society gallery in Bond Street. This long-famous venue, situated opposite Sotheby’s, slammed shut its doors, after more than a century of existence, very soon after Beal’s death. It now survives on the web, and also as a modest space in Edinburgh, but seems to have renounced any interest in contemporary art.

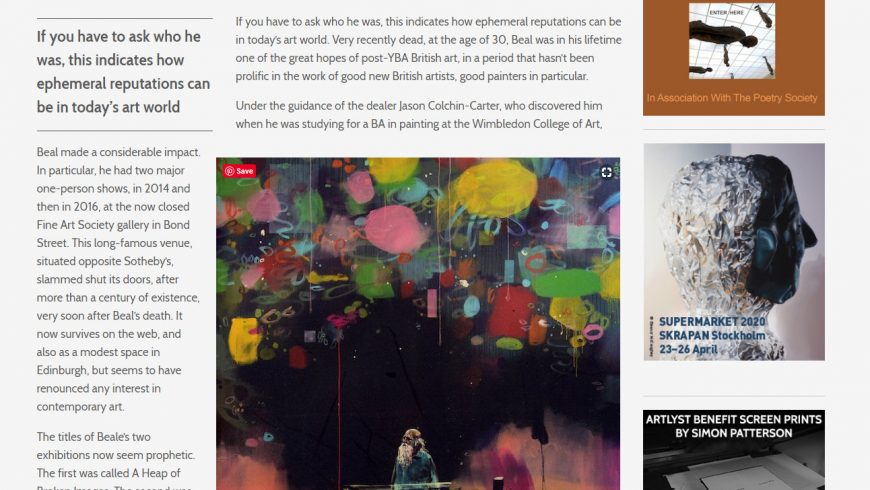

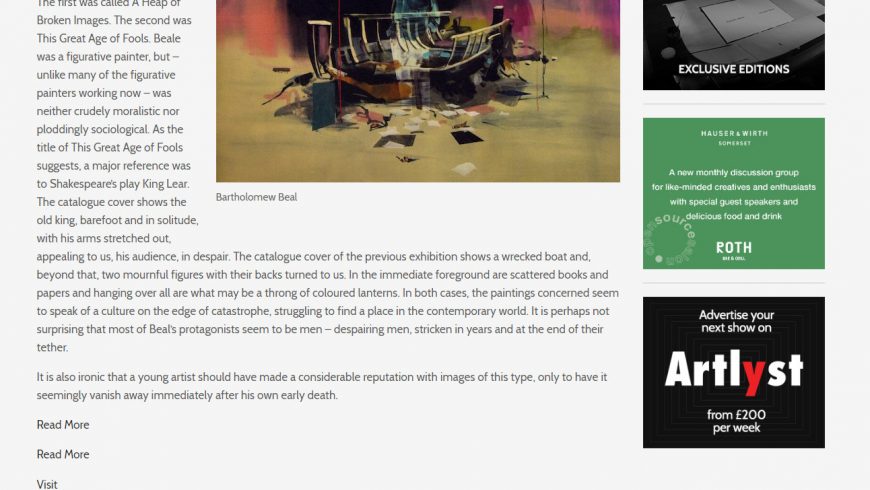

The titles of Beale’s two exhibitions now seem prophetic. The first was called A Heap of Broken Images. The second was This Great Age of Fools. Beale was a figurative painter, but – unlike many of the figurative painters working now – was neither crudely moralistic nor ploddingly sociological. As the title of This Great Age of Fools suggests, a major reference was to Shakespeare’s play King Lear. The catalogue cover shows the old king, barefoot and in solitude, with his arms stretched out, appealing to us, his audience, in despair. The catalogue cover of the previous exhibition shows a wrecked boat and, beyond that, two mournful figures with their backs turned to us. In the immediate foreground are scattered books and papers and hanging over all are what may be a throng of coloured lanterns. In both cases, the paintings concerned seem to speak of a culture on the edge of catastrophe, struggling to find a place in the contemporary world. It is perhaps not surprising that most of Beal’s protagonists seem to be men – despairing men, stricken in years and at the end of their tether.

It is also ironic that a young artist should have made a considerable reputation with images of this type, only to have it seemingly vanish away immediately after his own early death.